In the process of implementing the EAAL, each EU Member State has been pursuing its own priorities since 2012. In Slovenia, we focus on this in the EAAL Project. Occasionally, however, national coordinators meet at so-called PLA events. The first one was held last September, where we reported on successful ways to reach educationally deprived groups of adults; Slovenia hosted it. In March of this year, we wrote about the second PLA event on ‘Adult Learning Facing the Digital Revolution’, hosted by Belgium.

The topic of the third PLA event was the professional development of adult learning staff

Representatives of Austria, Estonia, Croatia, Ireland, Malta and Sweden brought together their experiences and views on this topic under the leadership of Denmark. The event took place online on 26 and 27 May with around 50 participants from most European countries. Martina Ní Cheallaigh, who has been in charge of implementing the EAAL at the European Commission all these years, gave the introductory presentation. At this event, however, she, unfortunately, said goodbye to our community due to retirement. The presentation was based on a text published in the 2019 Education and Training Monitor and our updates on the state and challenges of adult learning staff. The key finding is that it is a very heterogeneous, in most countries underrated community, which not only teaches but also develops educational programmes, advises and offers guidance to participants, performs promotional and administrative tasks and much more. And that is precisely the reason they need many competencies, which in some parts of Europe are acquired, at least initially, in formal education during the study of pedagogy or andragogy and later in non-formal forms of learning.

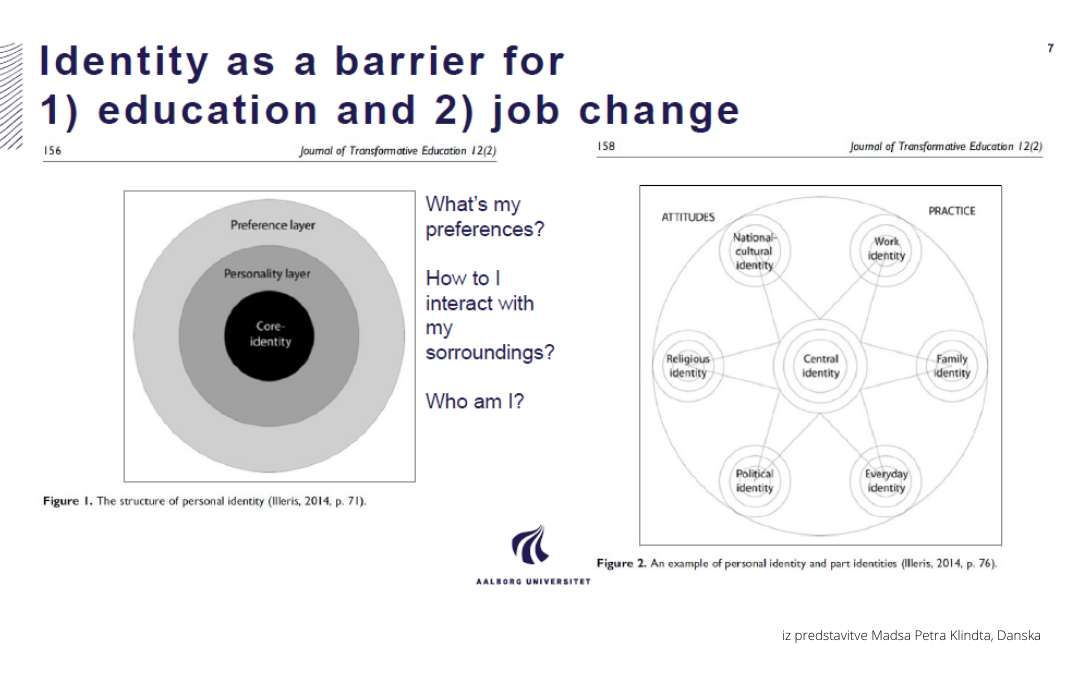

An excellent, high-quality education system, the possibility of further enrolment at any time in life, many support schemes etc., were the topics presented by the Danish Ministry of Education representative, Malene Vangdrup. Next was a plenary presentation by Mads Peter Klindt, a professor of political science, who emphasised the so-called Matthew’s effect. Those who are already highly educated and have good skills are continuing to learn, while others fall behind. He introduced the phrase ‘negative learning identity’ to point out that it is not all about motivating to join ALE but that obstacles must first be addressed. These usually result from past experiences and consequent negative attitudes towards learning. They need to be clearly defined and overcome by a holistic approach and acknowledgement of the knowledge and skills acquired in the past, usually in the work environment. Also, he emphasised the importance of guidance in ALE and the recognition of previously acquired knowledge.

The presentations of national education and training systems for adult learning staff from the countries mentioned above followed. Some lecturers focused on specific training to teach basic skills.

Attending the PLA event allowed me to tidy up and update the drawer in my head that says ‘adult educator’ and put some good news in it. For a start, the well-known thought popped into my mind: the profession of an adult educator is not recognised and appreciated; (almost) anyone can become one. Its professional identity is somewhat undefined, but at the same time, we expect the adult educator to be highly qualified in many areas and to possess a whole range of so-called soft competencies, which are usually key to being able to do their job well. Although I write in a gender-neutral form, the fact is that at least in Slovenia, there are many more women who practice this profession, which is probably also related to the fact that the profession is not clearly defined. In addition to top professional competencies or abilities, we expect that an adult educator also has highly developed general/generic, personal/personality, social, communication skills. And the list can go on. They must be capable of encouraging and empowering adult learners while effectively tackling the diversity of target groups they face. They must also be an expert in didactics for adult learners. Being a didactic myself, this caught my attention since I only heard what is already a known fact. In other countries, as well as in our country, there is undoubtedly not enough of this knowledge, and it is not available to adult educators in an enough systematic manner.

The common thread of the presentations were many examples of good practice, more or less of a project nature, insufficiently systemic and long-term oriented, with some decent attempts at certification or licensing that cannot yet be evaluated in the long run (Estonian example).

On the first day, we found out with our colleagues in a group discussion that even adult learning staff are not immune to lifelong learning. However, we are a little less conscientious and strict with ourselves than others when it comes to practice. As ALE experts, we know pretty well how long and arduous is the path to a goal that brings well-developed capabilities to encourage others to learn, give them feedback, create a suitable learning environment, provide them with a sense of acceptance, trust and adequacy, show them respect, acknowledge their educational path, life experience and acquired knowledge, recognise their educational barriers and perhaps special needs etc. Maybe also, or precisely because we know all this, adult learning staff need a carrot or a stick (if internal motivation is not present) to develop everything necessary. The theory is straightforward: teamwork, coaching, mentoring, supervision, etc. are processes that enable continuous professional growth; processes, development, etc., and not only short workshops, lectures and instant training.

I dare not write at this moment about what a systemic solution should be. The reason being that sometimes the breadth and diversity of our personal and professional competencies, combined with lifelong learning, acquired knowledge and skills, are what empower us most to do our job. My experience speaks for itself – I am a medical technician who became a biology and chemistry teacher and later received a Master’s degree in didactics of biology. I dare say that I am doing a pretty good job as an adult educator.

National framework for the development of basic skills of adults in Malta

The Ministry of Education in Malta representative, Christiane Fenech, presented the genesis of developing a very progressive national framework for developing basic skills in Malta, fully coordinated by the Ministry. In developing the framework, they relied on a study of the needs of adults to develop basic skills, existing measures and practical experience in this field in recent years and on a broad consultation on the necessary directions of development. The latter included adult educators, researchers, policymakers and various stakeholders. It turned out that the field is entirely undeveloped, left to the judgment and competence of individual providers. They discovered the need for a national curriculum in this field and for the training of teachers. They found an attractive solution to train teachers to teach basic skills, as they wanted to carry it out during the pandemic. They liaised with the EBSN and carried out the entire training as distance training using the MOOC developed within the EBSN. It is a collection of open educational resources that are based on the guidelines and recommendations of the European Commission’s Upskilling Pathways – new opportunities for adults. Teachers have very well received this form of teacher training. Also, it has generally been assessed as high quality and effective by representatives of the Maltese Ministry of Education.

George Koulaouzides, a dedicated adult educator, a lecturer at the Greek Hellenic Open University, expressed a reticent attitude towards education that takes place entirely online. He stressed that virtual forms of education are valuable in times of crisis, such as the one brought by the pandemic. Many times, in entirely different environments, it has been shown that teachers (regardless of the field) learn, think, develop their competencies and interact with each other better if they have the opportunity to collaborate and interact face to face. Human interaction cannot be replaced by any digital platform, regardless of how powerful it is. Adults and adult educators learn better when they have the opportunity to evaluate their experiences critically. Critical evaluation is a process that requires body and mind. He also reminded us that Malta is famous for renowned thinkers in ALE: Peter Mayo, Mari Brown, Karmen Borq. Their humanistic ideas are (were) inspiring even in times of isolation and changed the way of education during the pandemic. In conclusion, he summed up his thoughts and said that suppose we want to connect educators with each other and connect them into a professional community, then we need to enable close collaboration and live interactions.

The fourth PLA event on flexible forms of ALE, led by Norwayon 21 and 22 September (we will inform you about this in the next issue) concluded a cycle of such exchanges among EAAL national coordinators in the period 2020–2021. As this is a valuable and successful way of exchanging practices and views between the Member States, the PLA events will likely continue in the period 2022–2023.

Zvonka Pangerc Pahernik, MSc (zvonka.pangerc@acs.si), SIAE